A Little Bit about The Worlds of Little Edmund:

Some years back my son, who is autistic, was struggling to acquire speech. He was making some progress, but any time he got upset or frustrated, which was frequently, all his carefully but artificially acquired language skills went out the window. This left him more frustrated. On his own, he took to grabbing paper and crayons and drawing when this happened: d.i.y. art therapy. He didn’t necessarily draw what was frustrating or upsetting him; sometimes he did but the important thing, for him, was simply to draw. Another boy in his class, a friend of his, also drew tremendously – not just when upset, but all the time. Neither one was a Great Artist, but it was amazing to see what they made.

Sadly, a lot of children in our modern world are essentially thrown away. Adults around them can’t be bothered to listen, to look, to really see the remarkable people children already are. Adults do this to ordinary children; if a child has any kind of significant difference to whatever is considered “normal” they are usually even more dismissed as of no value.

So I created Little Edmund. Because I think all children are extraordinary, I think all people have value. The characters are cats partly because I’m fond of cats, and partly because when characters are animals we tend to look at their personalities and actions, instead of judging them by how they look or dress. We see better who they are, not who we think they are or ought to be. And Little Edmund is an artist because I was seeing first-hand the power of art.

The real medieval era, also called the Middle Ages, (roughly the years 1100-1500 c.e. – or a.d., if you like the old system) was an interesting but hard time. Most people didn’t have any luxuries, most people worked hard all the time. Even the people who were rich didn’t have things like running water. Paints didn’t come in tubes or bottles or little palettes. People had to make them themselves; grind up ingredients and mix them together. Many modern people sneer at the people of the Middle Ages, but they still had imagination and artistry... and everything had to be made by hand. Most of us don’t make things by hand anymore, but it’s an amazing experience to work with materials to create something. Since Little Edmund is a story about wonderful things coming out of things that seem ordinary or even defective, the medieval setting came naturally.

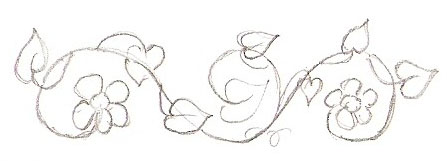

There are a lot of little details in the drawings (“illuminations” is the proper word) of The Worlds of Little Edmund. Medieval illuminators didn’t just illustrate things from the text. They tended to put in visual stories and jokes that might or might not have anything to do with the text they were drawing for, and I wanted to do some things like that. I make the seasons change over the course of the book. On one of the pages about the Knight I have little scenes of knightly life... though not always acted out by cats. There are often meanings to the plants or flowers. There aren’t any secret coded messages, but there’s a lot hidden in there, if one takes the time to look.

Some technical notes:

I didn’t intend to do the whole thing myself. I started with just a couple pages to show other people who might illustrate it the sort of thing I wanted. But then I couldn’t find anyone who wanted to illuminate the book, and I was rather having fun.

I didn’t have real parchment to use (it’s expensive and hard to find). I used paper that looked a bit like parchment.

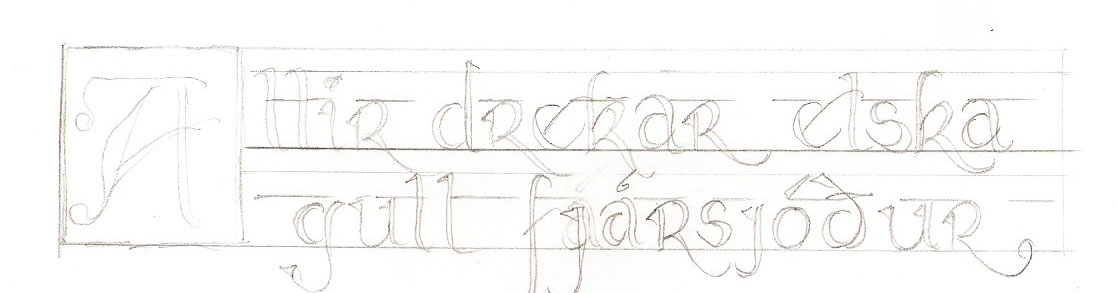

For each page, I lightly ruled on lines, and then pencilled in the text. Sometimes I had to erase a lot.

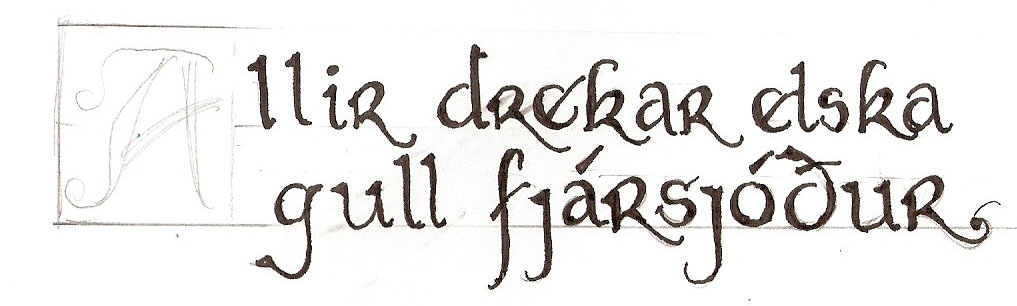

Then I went back and inked in all the words. I used, not an actual quill pen, but a pen with a metal nib and had to dip that in an ink-well. This is why some of the letters are thicker or thinner than others, darker or paler; it depended on how much ink was in the nib. Real medieval books, though far more elegant than mine, have the same effects if you look closely. They didn’t have pencils and erasers in the Middle Ages. They used chalk, and then brushed it away.

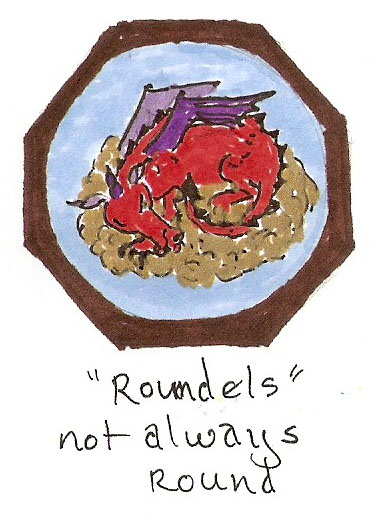

Then I pencilled in the illuminations. I usually started with any twining-vine-y stuff, and worked the “roundels” – those picture spaces, which often aren’t round – in after.

For the colours I used mostly water-colour paint, often without much water. Sometimes I inked in fine details (Sharpie ultra-fine markers worked well). For the most part I did not use a magnifying glass.

It took me an entire year to physically create the manuscript of the book. It was a lot of work.

And sometimes, despite my best efforts, things got smudged or messed up. And you can see that I got better at drawing as the book went along. I thought about re-doing pages or fixing some things. But the book is about, among other things, learning. It’s about things and characters changing, growing, finding out who they are. I like that the book shows that in itself. So I decided to leave it as it was.

If I had to do it all over again, there are some things I would do differently. I’d use white paper, for instance, because the ‘parchment’ paper made things really hard for the guys doing the actual printing of the book. I’d use a magnifying glass all along, because there would be so much more I could get in. I probably wouldn’t have the illuminations intertwine with the text. Real medieval books have the illuminations intruding on the text, which is part of why I did that. But it means that I couldn’t go back and change any text, and I can’t translate the story into another language without having to redo all the illuminations, because the text will space differently. So at the moment the book can only exist in English.

There is one language for which I would be willing to re-do the whole book. If anyone ever wants to translate it into that language, I would re-do the book with the differences I’ve described above. Then the book could be more easily translated into other languages, if people wanted that.

If you enjoy The Worlds of Little Edmund, please let me know! (See the “Contact” page.) And tell your friends. Or your local library. Thank you! And... why not try making a page or two... or more... of illuminated manuscript yourself?